It’s said that once you go vegan everyone around you suddenly turns into a nutrition expert. Never is that more true than when it comes to protein intake and never are people more uneducated.

First thing first: there’s no problem, what so ever, getting loads of protein as a vegan1.

Done.

You can close this article and go make yourself a tofu sandwich now.

No? Still here? Alright, we might as well elaborate on the topic and get geeky over vegan protein!

Table of contents #

I’m sure you’ve heard it.

But where do you get your protein?!

I believe this common knee-jerk reaction from omnivores stems from a common misconception. In many peoples’ minds, protein equals meat, like calcium equals milk, eating fat makes you fat and being cold will catch you a cold.

Which are all complete nonsense.

Meat is not protein – it has protein. But protein can be sourced from many, many other sources. In fact, protein isn’t so much a thing as it is many different varieties of things.

What is protein? #

Protein is one of the three primary macronutrients (the others being carbs and fat) and it’s an essential nutrient for the human body; being both a source of energy and one of the building blocks of body tissue.

Skin, muscle, brain cells, nails, and hair are some of our protein-based body parts. It’s estimated that about half of the human body’s dry weight is made up of protein.

Then you can understand why people are so worried about missing out on protein! Even though most don’t know what it actually is.

“I actually have no idea what protein is, but I’ve heard it’s like super important.”

- Random omnivore

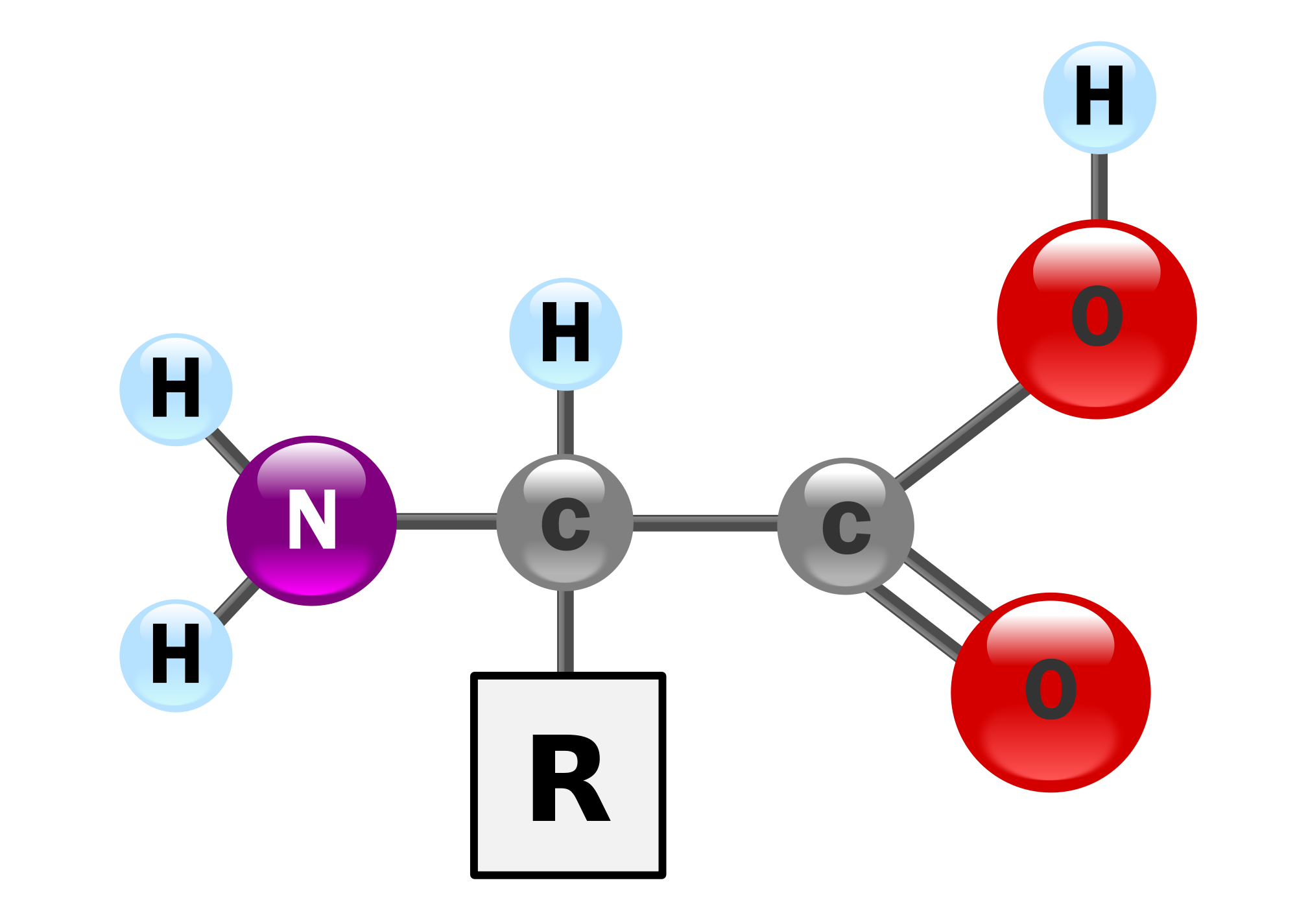

Amino acids #

In essence, proteins are made up of chains of smaller building blocks called amino acids – the actual magicians when it comes to this. Different combinations of amino acids give different proteins.

When we eat our bodies use an enzyme to break the protein down to its separate amino acids, which are then transported to the liver and used in three main ways:

- Protein synthesis. New proteins are assembled all the time and this is for example how we get our gainz.

- Energy. Carbs and fat are the major sources of fuel for our bodies but some of the energy we burn does come from protein, especially when not eating enough calories.

- Creating other substances; hormones like serotonin and adrenalin, for example.

We know of about 500 amino acids, but only 23 of them are so called proteinogenic amino acids – meaning they are used for building proteins – and just 21 of those are meaningful for human beings.

Essential Amino Acids (EAA) #

We can synthesize the majority of the meaningful amino acids – changing one type to another in our bodies. However, nine of them are essential amino acids and they must be part of our diets.

- Histidine supports healing wounds and the regulation of growth and natural repair mechanisms. It helps in forming blood cells and is very helpful during recovery after an operation or injury.

- Isoleucine increases your endurance and helps heal and repair muscle tissue and encourage clotting after an injury.

- Leucine is the only dietary amino acid that can stimulate muscle protein synthesis2. Gainz!

- Lysine plays an important role in the immune system.

- Methionine has antioxidant properties and can protect the body from toxic substances and free radicals.

- Phenylalanine is needed for normal functioning of the central nervous system. It has been used successfully to help control symptoms of depression and chronic pain.

- Threonine promotes normal growth by helping to maintain the proper protein balance in the body.

- Tryptophan is, among other things, transformed into serotonin (happy hormone) and further onto melatonin (sleep hormone), which both helps regulate your mood.

- Valine works together with isoleucine and leucine to promote normal growth, repair tissues, regulate blood sugar and provide the body with energy.

Branched Amino Acids (BCAA) #

A further subset of the essential amino acids are the branched amino acids (BCAA), named so because of their carbon branches. There are three of them: isoleucine, leucine, and valine.

(There are more, non-proteinogenic BCAAs, but we don’t care. This is an article about protein!)

Branched amino acids are often used to treat various diseases and injuries, but more interestingly for us is their ability to both increase protein synthesis and decrease catabolism (muscle breakdown).

BCAA helps build bigger muscles by attacking it from two fronts!

Normally you will see athletes supplement BCAA before training, as opposed to a full protein shake. With the latter your body needs to first break the proteins down to their amino acids before they can be used, whereas with already free amino acids you can more quickly boost the protein synthesis you get from the workout.

Protein quality #

So the difference between two proteins is their amino acid profiles – their combinations of amino acids. But how do we know which combinations are better? What protein should we try and eat more of and which less of?

American Institute of Medicine put together an advisory board to help us with exactly this. In 2005 their Food and Nutrition Board released the report Dietary Reference Intakes: Macronutrients which details the ideal amino acid profile for our bodies (milligrams per gram of protein):

Foodstuff with these proportions of amino acids is considered to be a source of complete protein. This includes legumes, seeds, grains, and veggies like chickpeas, black beans, cashews, quinoa, soy, etc.

There are sources that have a lot of some amino acids but little of others. For example, grain is normally low in lysine but high in methionine while legumes have the opposite proportion. By combining these, they can cover for each other and provide a complete protein intake.

Examples of this are beans and rice, lentils and pasta, hummus and pita bread, etc. Or my favorite: sandwiches with peanut butter! Vegan life is tough. ;)

Important note! This measurement of protein completeness has given rise to a myth that you need to combine plant based proteins in all your meals to stay alive as a vegan. This is provenly false3.

It might sound complicated, but it’s really not. This just means that you should not go on rice only-diet, or some exclusive peanut cleanse. That’s it really.

Bioavailability #

Looking at how complete a protein is, shows how it maps to our need of the various essential amino acids but it says nothing about how much of the protein we can actually absorb into our bodies. Depending on the protein, a chunk of it could just go out the other way.

This is where bioavailability comes into play.

There are a couple of different measurements of bioavailability but most look at the nitrogen balance between eating a protein. Since nitrogen is a fundamental component of amino acids, measuring nitrogen inputs and losses can be used to estimate bioavailability.

There are three major methods to measure bioavailability:

- Protein Efficiency Ratio (PER) looks at weight gain from protein intake.

- Net Protein Utilization (NPU) looks at protein intake and nitrogen excretion.

- Biological Value (BV) also looks at intake vs. excretion but in a stricter, more controlled way than NPU.

Some example values of Biological Value are soy bean 96%, egg 94%, soy milk 91%, quinoa 83%, rice 83%, tempeh 78%, beef 74% and tofu 64%.

That’s right – your body will more efficiently absorb protein from rice than it would that of beef.

It’s important to note that with all these measurements we can only get an estimate of the bioavailability of a given protein and these results show the maximum potential absorption.

That’s science speak for “it’s a pretty good guess”. :)

Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) #

The completeness of a protein and its bioavailability are two different aspects. They are both useful on a theoretical level but for our everyday needs we really just want to answer “what protein can I best stuff my face with?“.

Enter Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score – or PDCAAS for short – the end all, be all measurement for protein goodness.

PDCAAS looks at both how complete a protein is and how efficiently we can absorb it. Maybe you’ve heard bro scientists tout that egg is the top source of protein? This is the PDCAAS value speaking.

(Although that’s only half true, as egg only gets the highest score if you remove the yolk. And people are often unaware that soy protein is right up there with egg white in terms of protein awesomeness.)

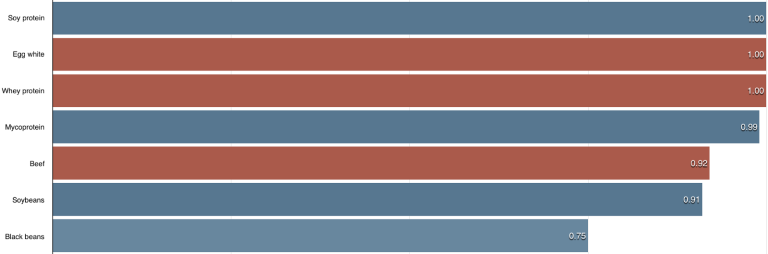

Some examples4:

The United Nations and the World Health Organization have both adopted PDCAAS as the preferred best method to determine protein quality, which shows how widely accepted this measurement is.

Reality is complex #

Protein completeness, biological value, and PDCAAS are all some really good measurements and it’s important to know the theory. However, we live in a more practical and complex world and must adjust accordingly.

For example, one beer won’t get you drunk. Nor will a glass of whiskey, some red wine, a shot of tequila or a gin and tonic. But when you have them all in one go? Now that’s a party.

All measurements of protein quality suffer from this same inherent flaw.

You can’t measure the efficiency of one single protein source and expect the result to hold true when you never actually consume only that source alone. If you really wanted to know you’d have to look at everything you eat, combined over a day or more.

The PDCAAS, BV or protein completeness of each source is practically limited.

Beans for example have a PDCAAS of 0.6 to 0.7, limited by low methionine but with more than enough lysine. Grains, on the other hand, have a PDCAAS of 0.4 to 0.5, limited by low lysine but with plenty of methionine. Combined in a veggie burrito, you’d have a PDCAAS approaching 1.

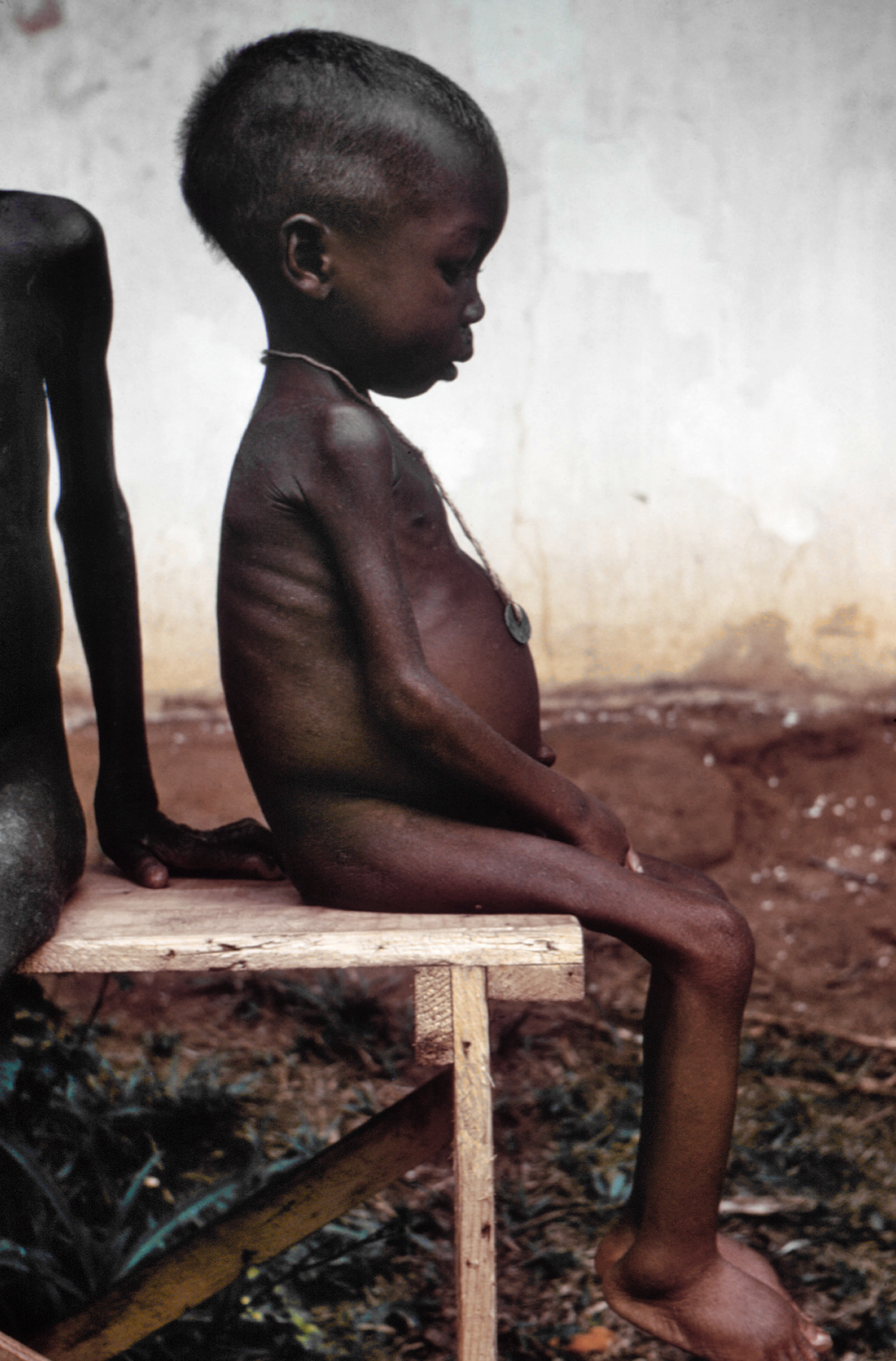

Protein deficiency #

So we know what kind of protein to eat and we have the tools to identify quality amino acid profiles. The next thing we need to tackle is quantity. How much protein should we eat?

We start with the lower end of the spectrum – not eating enough protein, leading to deficiency.

To be honest, this is something we are way more scared of than what is warranted. Kind of like fearing plane crashes when you’re more than sixteen times likely to die drowning in a bathtub (actual fact).

Being deficient in protein (also known as protein-energy malnutrition or protein-calorie malnutrition) is incredibly rare for otherwise healthy people. The few cases in the developed world are almost entirely found with small children as a result of stupid diets or ignorance of their nutritional needs.

Some symptoms showing that you might need more protein in your diet are hair loss, irritated skin, fatigue, etc. However, those symptoms could also have a variety of other causes.

Sleepiness, for example, could just as well be due to obesity, iron deficiency, lack of physical activity, alcohol or cigarette use, etc.

Don’t self-diagnose if you feel that something might be off! Always go see a proper doctor and get a blood sample, instead of jumping to easy conclusions.

Again, protein deficiency is extremely rare in our time and age. To believe that vegans risk deficiency just by virtue of not consuming animal products is ridiculous and only reveals a lack of nutritional knowledge.

Recommended daily protein intake #

Getting the right amount of any nutrition is a gradient. On one hand you have deficiency, on the other there’s excess and somewhere in between there is the sweet spot.

With nothing to aim for it’s hard to hit this bullseye, though. Luckily we have a very well-founded recommendation for our daily protein intake, thanks to a study by WHO.

The recommendation for healthy individuals is5 to eat 0.8 grams of protein for every kilo (or two pounds) of lean body weight. That equals 60 grams for a 75-kilo man and 48 grams for a 60-kilo woman.

This is the recommended value and not a minimum one!

Pregnant or breastfeeding women and people over 70 years need a little more protein and should strive for 1 gram per kilo lean body weight.

60 grams of protein could be distributed like 15 grams for breakfast, 25 grams for lunch and 20 grams for dinner. As a vegan, you’ll have to put effort into NOT getting these amounts by just eating regular food.

There’s a myth saying we can only absorb 30 grams of protein per meal. It comes from the fact that 30 gram is the upper limit for how much we can boost our protein synthesis and so people have simply misunderstood. This boost is just one small of many benefits of eating protein – you’ll still make use of all those protein building blocks.

Vegan protein sources #

Now on to the (vegan) meat of this article! Here are some high protein vegan sources:

Big thanks to Miki Mottes for creating and letting me share this awesome graphic here.

NB! These numbers are all for cooked or prepared foodstuffs – as you’re actually eating them. Normally their protein values are even higher but because of boiling, there’s simply more water weight per 100 gram.

Looking again at our examples with the 60 grams of protein for a 75 kilo man and 48 grams for a 60 kilo woman – how much food would they have to eat to reach the recommended amount of protein?

With the above chart, we can see that a handful of peanuts and a piece of tofu for lunch would cover it for the woman. Add in a dinner with some rice and lentils and the heavier man would be set.

Reaching the recommended amounts of protein as a vegan is obviously not hard at all.

Optimal protein intake #

The recommended amount of protein is all well and good for the average citizen. But we’re not trying to be average, are we? If we want the strength of a gorilla, we can’t eat like a chimpanzee!

So what is the optimal amount of protein for building muscle?

I’ve found three studies6 7 8 that suggest a wide range of deviation from the recommended 0.8 gram per kilo lean body weight. The lowest suggest increasing it to 1.6-2.0 grams while the highest goes as far as 2.3-3.1 grams.

This is for maximum effect to supplement heavy strength training and body building.

The extra effect from stepping up your daily protein intake beyond RDI seems to be very small and with diminishing returns – it gets smaller as the amount increases.

I personally try to eat around 2 gram per kilo myself. At 80 kilo that could mean:

- Porridge with peanut butter (29 g) for breakfast.

- Beans (22 g) and rice for lunch.

- Tofu (38 g) and veggies for dinner.

- A couple handfuls of peanuts (26 g) for a snack.

- One protein shake (36 g) after working out and another at night.

That’s at least (29 + 22 + 38 + 26 + 2*36 =) 187 grams of protein.

Summary #

So where do you get your protein? From regular vegan food! Legumes, grains, nuts and seeds.

Which sources are the best? Soybeans, seitan, quinoa, chickpeas, tofu, tempeh, and nuts.

How much protein should I eat a day? At least 0.8 gram per kilo lean body weight, but preferably 2 g/kg.

Do I have to worry about protein? Not at all – you most likely already eat enough.

Then why should I think about protein? Deliberately eating more can boost your results (a bit).

Now over to you – do you still wonder about anything concerning vegan protein? Did I miss something? Join Athlegan (for free), write me your question and I’ll keep this article updated!

- “Vegetarians are able to get enough essential amino by eating a variety of plant proteins.” http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/002467.htm↩

- “The Leucine Content of a Complete Meal” http://jn.nutrition.org/content/139/6/1103.abstract↩

- “Plant proteins in relation to human protein and amino acid nutrition” http://ajcn.nutrition.org/content/59/5/1203S.abstract↩

- “Protein – Which is best?” http://www.jssm.org/vol3/n3/2/v3n3-2pdf.pdf↩

- http://journals.humankinetics.com/ijsnem-back-issues/IJSNEMVolume16Issue2April/AReviewofIssuesofDietaryProteinIntakeinHumans↩

- “International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: protein and exercise” http://www.jissn.com/content/4/1/8↩

- “Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: nutrition and supplementation” http://www.jissn.com/content/11/1/20↩

- “Protein and amino acids for athletes” http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14971434↩